This is an exciting post for me to write, mostly because it’s one of those subjects that misinformed people and broscientists think they absolutely know everything about.

When, as usual, they don’t even know the half of it.

Muscle Fiber Types and the Training Techniques

Muscle fiber types and the training techniques to grow their size, increase their number or increase their strength is the basis of a lot of weight lifting talk, both in and out of the gym.

Of course it’s been a subject scientists have been interested in getting to the bottom of, not to mention professional athletes and coaches.

Can you train in a way that increases your slow-twitch (Type 1) or fast-twitch (Type 2) muscle fibers? Or will you be making a workout mistake and wondering why you are not making the muscle gains.

The age-old broscience response is, of course:

low-rep count with high weight/load for fast-twitch fiber growth; and …

high-rep count with low weight/load for slow-twitch fiber growth

You’ve probably also heard it said that Type 1 (slow-twitch) are predominantly activated for muscle endurance, and Type 2 (fast-twitch) for short spells of high power and strength.

You may even have come across some sage advice about which muscles are type-I or type-II dominant, and how to train them thusly.

So, what’s true, what’s almost true and what is BS?

Continue reading, and you might just be surprised what you get out of it, specifically in terms of directly applicable and practical tips for your weight training.

Muscle Fiber Types 1 and 2 – An Overview

There are two main types of muscle fiber.

- Type 1 = Slow-twitch fibers

- Type 2 = Fast-twitch fibers

There’s also two basic sub-categories of Type 2:

- Type 2A

- Type 2X

Type 2A are somewhere in between Type 1 and Type 2X.

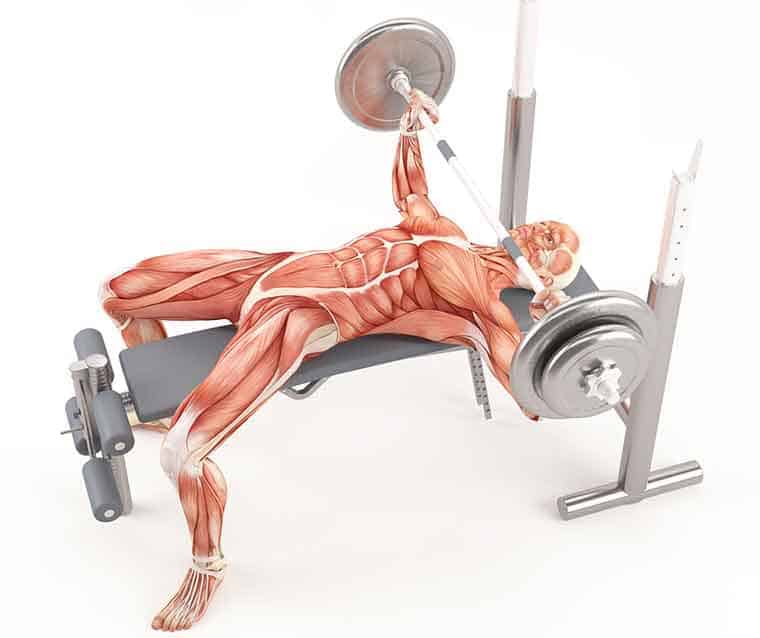

The force output requirement of the task you are performing determines which muscle fibers are recruited by your nervous system.

It happens in a sequence called the Principal of Orderly Recruitment, starting with Type 1 fibers activating in greater and greater numbers until Type 2 are brought in.

If the load/force requirement keeps increasing, your muscle will ultimately reach the point of failure when there are no more Type 2 to recruit.

Type 1 fibers take the longest to fatigue, which is also why they are the principal muscle fiber type used in endurance sports like triathlons and marathons.

It’s also why the theory of low weight – high reps training is a logical approach for growing Type 1.

When you lift heavy weight, the first few reps recruit mostly Type-2 fibers, so that training type for that muscle type obviously follows.

Type 2X fibers are even more powerful than type 2A but they endure much less again. For training purposes, they are not very useful because their time of effect is extremely small, as is their proportion in trained muscles.

Therefore, when resistance training and other physical exercise is discussed, any muscle fiber talk will refer to Type 2A.

Both Type 1 and Type 2 can produce about the same amount of force per unit of area.

That’s interesting because people often think force and power are interchangeable, and also that Type 1 muscles shouldn’t be able to exert the same force as Type 1.

It’s true that Type 2 are more powerful but that’s because they can exert the same force over a shorter period of time.

Training and Muscle Fiber Growth

Different training triggers different growth responses in type 1 and 2 muscle fibers.

Resistance training, more accurately strength training, tends to elicit a higher growth response in Type 2 fibers by a quarter to three quarters more than in Type 1.

Athletes who train for and compete in power dominated sports such as the shot put or sprinting have a higher proportion of Type 2 fibers.

Likewise, endurance athletes like distance runners, cyclists and triathletes grow more Type 1 compared to Type 2.

Endurance sports and type 1 muscle draws energy from fat storage and oxygen, whereas sprinting 100m is requires anaerobic respiration fuelled by glycogen and phosphocreatine stores.

It might seem odd then that proportions of Type 1 to Type 2 fibers in bodybuilders and lifters are roughly the same as they were before they started training.

So what does that mean for your muscle fiber types? And, more importantly, how can you use it to your advantage with respect to your training?

The answer to the first question is: if your weight training is the dominant part of your program, then you most likely have a fairly even split – 50/50 – of Type 1 to Type 2 muscle fiber, with perhaps Type 2 having the edge.

The answer to the second question is more interesting.

You may have read my article about concurrent training and part where I discuss quadriceps training, particularly the observational study that saw quads grow larger in response to strength training plus endurance training compared to strength-only training.

It now seems more obvious why this would be the case. Your quads are roughly 50% type 1 and 50% type 2. It might stretch to 60/40 from one individual to another but the proportions are close enough to make the following argument:

Concurrent training builds bigger quads than focused strength-only training because it’s building both muscle fiber types equally.

Now, take most muscles you train and try and work their Type 1 fibers out using a treadmill or a static bike and you’re going to look extremely silly.

That’s where we come back to the low weight – high reps style of training.

To maximize growth, at least from the perspective of muscle fiber type, which definitely has an impact on size and strength of the muscle, perhaps a mixture of high load and low load training is a good idea.

An Interesting Muscular Exception

There are some muscles that don’t have an even split of muscle fiber types. Mostly they are those muscles with functions irrelevant to training such as tiny fast-twitch eye muscles.

There is one “macro” muscle that can be 80% to 90% Type 1 (slow-twitch), and that’s the soleus.

The soleus is one of your calf muscles – not the gastrocnemius, which are higher up and recognized by their tell-tale “split” when they are well developed. The soleus is on the inside of these and extends most of the way down your achilles tendon.

You can always tell a runner from their well developed soleus muscles.

Training Specificity Based on Individual Muscle Fiber Proportions

As always, it comes back to what you want to get out of your training. As far as performance goals are concerned, it’s fairly easy.

if pure strength is your goal then you have to lift heavy and often and, at some point in the near future, increase the weight. Your muscles overcompensate and grow in order to be able to handle that kind of weight better then next time.

For strength gains in the 85% 1RM and above kind of training, the growth will largely take place in the form of myofibrillar hypetrophy – basically the contractile proteins in your muscle fibres.

The degree of Type 2 fiber development will probably exceed Type 1 but don’t forget that powerlifting athletes – who live for the squat, deadlift and benchpress triple – end up having proportions of type 1 to type 2 that are similar to the un-trained Joe.

Endurance athletes will train primarily in the realm of their chosen sport, be it running, cycling, triathlon or whatever. The distance, time, fuel requirements and so on will undoubtedly lead to greater Type 1 development, and of this there is little doubt.

Bodybuilding, where size of muscle growth takes an equal or even greater priority than strength, it seems appropriate to mix your training methods up as I mentioned earlier

But what about your body type, and muscular make-up?

It’s fine to say that on average, muscle doesn’t tend to have overly unbalanced proportions of muscle fiber types, and training specifically for Type 2 doesn’t even seem to change that very much.

However, there are exceptions. And those exceptions probably play a role in an athlete becoming exceptional at one sport or another.

So, can you somehow find out what type of sport or training you’d be more suited towards, based on your muscle fiber proportions?

And, can you actually convert your muscle fiber type from one to another?

The answer to both questions is, not really.

In terms of finding your Type 2 fiber proportions for example, your different muscle groups might be slightly different, so that talking about your quads might not be relevant for your chest.

Secondly, this has been investigated in a couple of studies (here’s one of them…oh, and here’s the other), where scientists sought to discover whether there is a connection between proportions of muscle fiber type and the amount of repetitions a weight lifter can perform at a certain (usually high) percentage of their one rep max (1RM).

These studies were attempts to verify or debunk theories that lifting 85% of you 1RM for 6 reps or more means you are Type 1 dominant, lifting less than 4 reps, you’d be Type 2 dominant and anywhere between that would mean you have an even spread.

The flaws in the theory are plentiful, and doesn’t address the glaring issue of what a Type-1-dominant person compared with a Type-2-dominant person’s maximum single lift (1RM) would be if all other factors were equal.

Similarly the number of reps you can do varies exercise to exercise even using the same muscle group. For example, I can do more reps of 85% of my leg press 1RM than I can of my squat 1RM.

Skill is another massive factor. Someone who’s squatted for a year won’t be as skillful in the movement as someone who’s done it for a decade. Skill development in the case of compound lifts refers to many factors, including technique, neurological adaptation, support muscle growth, nervous system function and flexibility.

Going back to those studies, the second one even involved taking biopsies (samples) of the muscle tissue itself. That study (Terzis et al) found less of a correlation to reps at % of 1RM than the previous one (Douris et al), and that wasn’t very convincing.

The Douris study should a significant correlation of repetitions and weight to type 2 muscle fibres but it was so small as to be virtually insignificant.

And the more invasive study was even less impressive. It found that only 4% of the difference in lifting certain weight at certain reps was down to the participants’ muscle fiber types.

Summarize That Last Section, Please

Basically, you’d have to go and get chunks taken out of every one of your muscles and lab tested to get even a slightly accurate idea as to their fiber type proportions.

And, it would have to be more than one chunk from each – to get an average spread, because muscle fiber type can change across the span of muscle tissue.

No-one should have that procedure done, and it’s not clear from lifting weights at this or that percentage of your one rep max whether you are Type 1 or Type 2 dominant.

So don’t bother.

To answer whether you can convert you muscle fiber from type 1 to type 2 – again, not really.

Some kind of extreme muscle damage can cause it to happen, as can old age, but neither of those things are relevant to a person looking to improve physique and strength healthily (that would be you).

Conclusion – Muscle Fiber Type – Go Big, Go For Both

For me, it all comes down to how you use the knowledge you have. Now you know a little more than you did about Type 1 “slow-twitch” and Type 2 “fast-twitch” fibers.

Perhaps you are more enlightened than before, or perhaps I have confused you. I’m sorry if it’s a case of the latter.

I try and write these things as concisely as possible, but oftentimes brevity doesn’t help the subject matter stick, it just leaves more questions than answers.

My answer to the muscle fiber debate is to pursue the path most obvious. We have two main types of muscle fiber. Training them both will stimulate both to grow.

If size and strength are important to you, this should be good news. Instead of focusing entirely on high-rep-low-load or low-rep-high-load training you can do both. Variety being the spice of life, I hope that is music to your ears.

Still, depending on your primary goal, you can have a dominant focus in your training, and a secondary focus. If increasing your maximum lift is your main goal then you should primarily attack your high-load training, with some high-rep thrown in.

Perhaps your main aim is to be a massive brute. If so, primarily focus on moderate-high rep training with some heavy low-rep stuff on top.

The beauty of all of this is that you no longer have to limit yourself to certain lifting practices to make headway, and you don’t have to think in terms of fast-twitch or slow-twitch.